Attachment and the Nervous System

The first few years of life are a critical period for brain development, and the quality of early childhood attachment experiences significantly shapes the nervous system in a way that persists through adulthood.

Our nervous system regulates our emotions and physiological responses to things going on around and inside us; it determines whether we feel safe and relaxed, anxious and hyper-vigilant, or numb and detached.

From an early age our nervous system gets wired into characteristic patterns of activation and response, so it can feel very much like we just get hijacked by strong thoughts, feelings and physical sensations, and because these patterns are so entrenched they can feel impossible to change.

Re-tuning your nervous system is certainly difficult but definitely possible, and having an in-depth understanding of your patterns is the first step to changing them.

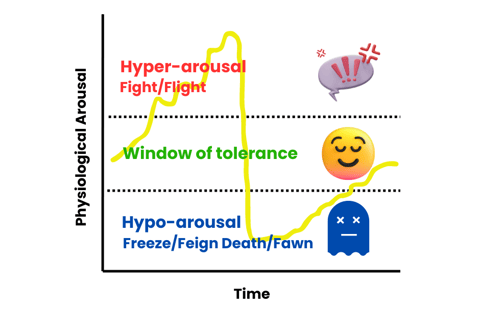

Simply put, the nervous system is designed to detect threats in the environment and to mobilise us to safety. There are three key states; the window or tolerance, hyper-arousal, and hypo-arousal.

The Window of Tolerance

This is the optimal state of regulation, the threat-detection system is inactive and the brain is in learning mode, able to be curious about the environment and to reason and process stimuli without becoming dysregulated. Breathing and heart rate are normal, and digestion and other bodily functions are unimpeded.

Healthy development of the nervous system depends on having secure attachment figures that can support the child to co-regulate, which makes use of mirror neurons to bring the nervous system back into the window of tolerance.

Mirror neurons are like an internal antenna that pick up on the state of the nervous systems of others, and tune our system into alignment with them.

Caregivers that model healthy ways of coping with stress and difficult emotions soothe the child and support the development of a nervous system that has a wide window of tolerance, able to cope with a range of emotions and experiences without becoming dysregulated.

Hyper-Arousal

This state occurs when a threat is detected and the sympathetic nervous system is activated. The threat in question may be a legitimate source of danger in our environment, or it could be (and often is) a product of our own internal process.

The brain does not know the difference between a tangible threat and our imagination or interpretations, and it responds to strong thoughts as if they were real.

In hyper-arousal our bodies are mobilised to evade danger, adrenaline floods our system, oxygenated blood is diverted to our limbs to prepare us to fight or flee, heart rate and breathing become rapid in readiness for intense exertion - this is the fight/flight response.

Thoughts feel panicked, chaotic and disordered as the brain is in survival mode. If physiological arousal continues to escalate a panic attack may be triggered. This state is only designed to last for a short time to get us out of danger, but those who suffer from an anxiety disorder can be chronically stuck in this state, albeit at varying levels of intensity.

Those brought up in the kind of volatile and unpredictable environment that breeds an anxious attachment style might spend much of their time in a state of hyper-arousal; the child is constantly trying to anticipate changes in their caregiver’s mood which locks them in a state of hyper-vigilance.

Such a child would grow up to have a small window of tolerance with a high baseline level of arousal, meaning that it takes less for them to be triggered into dysregulation. People like this might experience frequent fatigue, body pain, headaches, stomach issues, panic attacks, mood swings and jumbled thoughts.

They are constantly in or approaching survival mode and this is exhausting for the system as the constant flood of adrenaline disrupts processes like sleep and digestion. Breathing is consistently more rapid and shallow than it should be so vital oxygen is not getting to the brain for optimal functioning.

This has a cumulative effect throughout life as it makes it difficult to perform cognitively, manage life challenges and have healthy relationships. This impacts on people's self-esteem and core beliefs about themselves, which can create patterns of self-sabotage.

Hypo-Arousal

This state is triggered when the brain is flooded with stimulus that it cannot process, the level of threat is deemed too severe for escape and the freeze/feign death response is triggered.

Limbs become either rigid or floppy, breathing and heart rate drop, the body may feel paralysed and the brain produces a rush of pain-relieving endorphins. It can feel like the mind separates from the body as you become numb and dissociated.

A traumatic event such as an assault or robbery often puts people in this state. This is part of what makes such trauma difficult to process, people freeze in the moment and are unable to escape, and they may blame themselves afterwards for not defending themselves. When the nervous system goes into this state you are immobilised and have no control, your system shuts down to protect you.

Triggers that remind you of the trauma, which can be very innocuous and unconscious, such as a person wearing a similar sweater to the attacker, can cause you to re-experience the trauma and go into a state of hypo-arousal.

Hypo-arousal can also manifest in the more subtle fawn response, the human equivalent of a dog showing submission by rolling over to expose its belly. With Fight/Flight circuits disabled your nervous system can prime you to be more acquiescent and geared to appease. This function has played a very important part of our evolution as social creatures but it can be compounded by unhelpful self-beliefs into a chronic pattern of people-pleasing.

People brought up in an environment where they were given insufficient nurturing and learned to self-soothe, ie. those with a typically avoidant attachment style, may tend towards this state.

They may frequently feel detached, lethargic and spacey. They might find it hard to get excited about things or indeed feel much of anything at all.

Those prone to hypo-arousal might typically withdraw and isolate themselves, have a hard time asserting boundaries due to the fawn response, and may experience bouts of or persistent depression.

Picture shows a graph with physiological arousal on the y axis and time on the x axis. A line begins in the middle of the y axis in the window of tolerance, it tracks upwards with peaks and troughs and escalates into hyper-arousal, once it reaches the upper limit it plummets down into hypo-arousal, where it flatlines for a time before trending back upwards into the window of tolerance.

The graph above shows a typical pattern of physiological arousal in the event where a state of rising anxiety trips into hyper-arousal triggering a panic attack, which in turn causes the nervous system to shut down into hypo-arousal, where there is a period of some dissociation before gradually returning to the window of tolerance.

Notice that as physiological arousal is escalating there are peaks and troughs, this is very common as usually during a period of rising anxiety there are moments of distraction when thoughts shift elsewhere and the nervous system settles a bit.

This is powerful to know, as your thoughts absolutely influence your physiology, and dwelling on and catastrophising a problem creates this escalating physiological response where your heart rate and breathing speed up and adrenaline starts flowing.

During this period of escalation, if you can notice how your thoughts and nervous system are racing, you can make use of strategies to calm and settle yourself.

However if things continue to escalate there comes a point where the frontal lobe, the part of the brain responsible for higher-level processes like logic and reason, goes offline and the system flips into a state of panic, of which the only way out is through.

In the next post we will go into more detail about how you can learn to gauge your own levels of physiological arousal and understand your own patterns, and strategies you can use to bring yourself back into the comfy window of tolerance.